Thalassemia is an inherited blood disorder that affects the body’s ability to produce hemoglobin and red blood cells.

A person with thalassemia will have too few red blood cells and too little hemoglobin, and the red blood cells may be too small.

The impact can range from mild to severe and life-threatening.

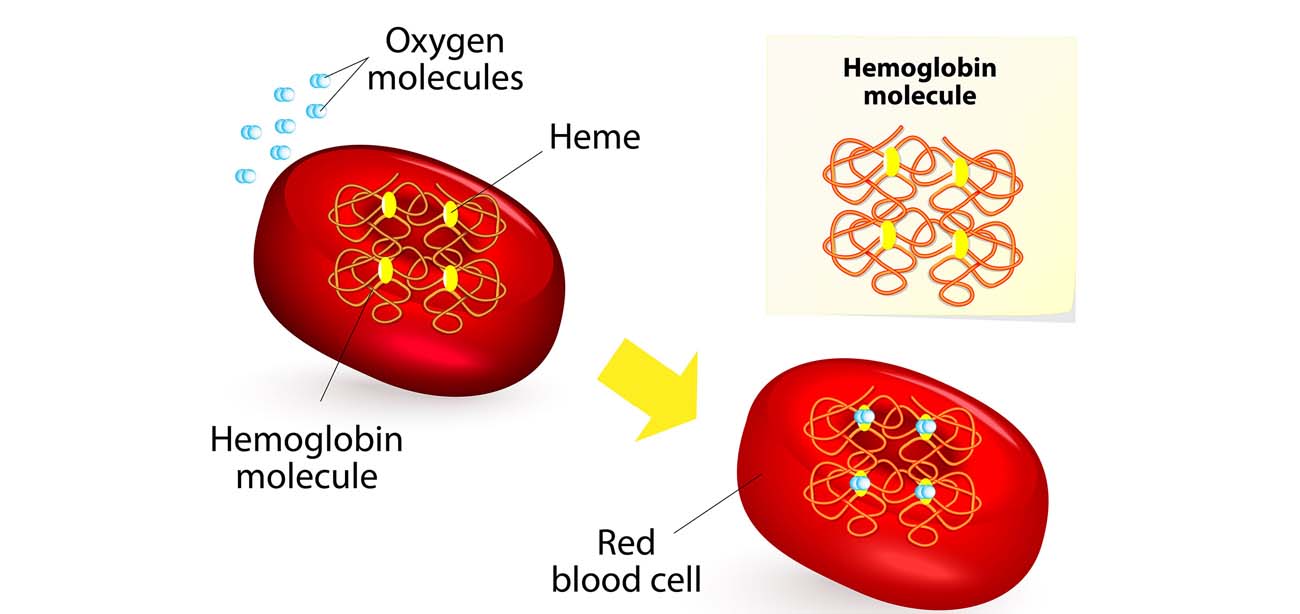

Four alpha-globin and two beta-globin protein chains make up hemoglobin. The two main types of thalassemia are alpha and beta.

Alpha thalassemia

In alpha thalassemia, the hemoglobin does not produce enough alpha protein.

To make alpha-globin protein chains we need four genes, two on each chromosome 16. We get two from each parent. If one or more of these genes is missing, alpha thalassemia will result.

The severity of thalassemia depends on how many genes are faulty, or mutated.

One faulty gene: The patient has no symptoms. A healthy person who has a child with symptoms of thalassemia is a carrier. This type is known as alpha thalassemia minima.

Two faulty genes:The patient has mild anemia. It is known as alpha thalassemia minor.

Three faulty genes: The patient has hemoglobin H disease, a type of chronic anemia. They will need regular blood transfusions throughout their life.

Four faulty genes: Alpha thalassemia major is the most severe form of alpha thalassemia. It is known to cause hydrops fetalis, a serious condition in which fluid accumulates in parts of the fetus’ body.

A fetus with four mutated genes cannot produce normal hemoglobin and is unlikely to survive, even with blood transfusions.

Alpha thalassemia is common in southern China, Southeast Asia, India, the Middle East, and Africa.

Beta Thalassemia

We need two globin genes to make beta-globin chains, one from each parent. If one or both genes are faulty, beta thalassemia will occur.

Severity depends on how many genes are mutated.

One faulty gene:This is called beta thalassemia minor.

Two faulty genes:There may be moderate or severe symptoms. This is known as thalassemia major. It used to be called Colley’s anemia.

Beta thalassemia is more common among people of Mediterranean ancestry. Prevalence is higher in North Africa, West Asia, and the Maldive Islands.

Treatment depends on the type and severity of thalassemia.

Blood transfusions: These can replenish hemoglobin and red blood cell levels. Patients with thalassemia major will need between eight and twelve transfusions a year. Those with less severe thalassemia will need up to eight transfusions each year, or more in times of stress, illness, or infection.

Iron chelation:This involves removing excess iron from the bloodstream. Sometimes blood transfusions can cause iron overload. This can damage the heart and other organs. Patients may be prescribed deferoxamine, a medication that is injected under the skin, or deferasirox, taken by mouth.

Patients who receive blood transfusions and chelation may also need folic acid supplements. These help the red blood cells develop.

Bone marrow, or stem cell, transplant:Bone marrow cells produce red and white blood cells, hemoglobin, and platelets. A transplant from a compatible donor may be an effective treatment, in severe cases.

Surgery:This may be necessary to correct bone abnormalities.

Gene therapy:Scientists are investigating genetic techniques to treat thalassemia. Possibilities include inserting a normal beta-globin gene into the patient’s bone marrow, or using drugs to reactivate the genes that produce fetal hemoglobin.